Twenty million developers. That’s how many people worldwide get to decide what software the rest of us use. The ratio is absurd. Flip it around: what if only 20 million people could upload videos to YouTube, publish on Medium, or share photos on Instagram? We’d lose the chaotic, endlessly surprising internet we know.

Software creation remains locked behind technical gatekeeping. Most people consume apps built by a coding elite, never creating tools for their own needs. Enter Eugenia Kuyda, founder of AI companion app Replika, who just launched Wabi with $20 million from some of Silicon Valley’s sharpest investors. Her pitch? Make software creation as simple as posting a video.

Wabi aims to become the YouTube of software—letting anyone generate AI-powered micro-apps through text prompts. No coding. No technical knowledge. Just ideas turned instantly into functional applications. This isn’t vaporware. It’s a live platform already generating buzz across social media, with early users building everything from motivational quote apps to custom fitness trackers in minutes.

What Is Wabi? The Platform Aiming to Be the “YouTube of Software”

The premise sounds almost too simple. Describe the app you want in plain English. Wabi generates it immediately. Want an AI therapy companion? Type it in. Need a fitness tracker customized to your exact routine? Done in seconds. The platform handles user interface design, backend logic, database structure, even the icon.

This is what Kuyda means by YouTube of software. Just as YouTube democratized video creation, Wabi aims to democratize app building. The $20 million pre-seed round—from Naval Ravikant, Garry Tan, Justin Kan, Amjad Masad, Akshay Kothari, DJ Seo, and Sarah Guo—signals serious conviction.

Why would these legendary tech figures bet so heavily on a consumer AI app creator? They recognize massive untapped demand. Current micro-app platforms serve developers almost exclusively. Wabi flips that equation, targeting everyday users who’ve never written code. The no-code AI movement has gained enterprise traction. Wabi brings it directly to consumers.

The Natural-Language Interface Changes Everything

Traditional no-code tools still require understanding workflows, integrations, logic trees. Wabi eliminates even those minimal barriers. Users describe what they want. AI handles the translation from intent to execution. The platform generates not just basic functionality but polished, complete applications ready to use and share.

From Replika to Wabi: Eugenia Kuyda’s Long-Term Vision for Personalized Software

Kuyda’s track record makes this ambitious play credible. She founded Replika in 2017—five years before ChatGPT entered public consciousness. Conversational AI seemed like science fiction to most consumers then. Yet she built the world’s first mainstream AI companion app. Today, Replika serves 35 million users. That early bet on consumer AI paid off because she understood where the technology was heading.

Her conviction about language models traces back further. In 2012, a friend at Google DeepMind introduced her to word2vec, the first technology that could represent words as mathematical vectors. For someone raised on Wittgenstein’s philosophy—particularly his assertion that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world”—the implications were profound.

Language, not vision, would unlock true AI understanding. While the broader tech world fixated on image recognition breakthroughs like ImageNet, Kuyda founded a company dedicated to language models and dialogue generation. Years before the research infrastructure even existed to support such work.

The Long Road to Transformer Models

When Google researcher Quoc Le published the first paper on applying deep learning to conversation in August 2015, Kuyda’s team immediately pivoted their entire company. The paper didn’t include a working model—just promising sample outputs. But they saw the future.

That future took seven years to materialize. The team struggled through the pre-Transformer era, when training dialogue models required enormous datasets and could only handle basic conversation. The experience taught Kuyda a crucial lesson: spotting trends early matters, but you also need capital and conviction to survive the gap between vision and reality.

By 2020, OpenAI invited Kuyda’s team to San Francisco as one of the first GPT-3 API partners. Mira Murati and Sam Altman demonstrated capabilities that seemed magical. Zero-shot learning that could handle any task, from writing tweets in specific voices to translating text. Replika became the GPT-3 API’s largest customer, positioning itself as the only consumer chatbot using genuinely generative AI at scale.

The Interface Determines the Use Case

Running Replika exposed a paradox. Despite the remarkable capabilities of GPT-3, and later ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini, most users deployed these tools for remarkably narrow purposes. Look up information. Draft emails. Help with homework. OpenAI’s own research confirmed this—roughly one-third of all use cases involved writing assistance.

The problem wasn’t the technology. It was the interface. When users see a command line or chat window, they mentally categorize the tool as a search engine or writing assistant. The interface’s “affordance”—what it suggests you can do with it—constrains user behavior. Unlocking the full potential of language models requires a different interface entirely. Something more visual, more interactive, more intuitive than an empty text box.

This insight about personalized software became Kuyda’s next bet. If the interface determines how people use AI, then building the right interface could unleash entirely new categories of usage.

The Interface Problem: Why Current AI Feels Like MS-DOS

Kuyda and her team became obsessed with a historical parallel: modern chatbots occupy the same position as MS-DOS in the evolution of personal computing. The comparison might sound grandiose. The underlying logic is sound.

DOS required memorizing arcane commands. Only a small technical minority could use computers effectively. Windows and MacOS changed everything by introducing graphical interfaces that made computing intuitive. Point. Click. Drag. Drop. These simple interactions unleashed the personal computer revolution because they lowered the skill floor dramatically.

The AI Paradox of Mass Adoption

Today’s chatbots already have massive reach—nearly a billion users worldwide. Yet those users overwhelmingly stick to basic tasks. The models can do far more, but the interface limits what people think to try. This creates a strange situation where AI has achieved mainstream adoption without unlocking its mainstream potential.

What’s needed is an interface that makes AI’s broader capabilities feel as natural as clicking an icon. The “Windows moment” for AI won’t come from better models. It’ll come from better interfaces that help non-technical users understand what’s possible.

This is where Wabi enters. It’s not a code-generation tool for developers or a prompt-engineering playground for power users. It’s deliberately designed for people with zero technical background who simply want to solve problems in their daily lives.

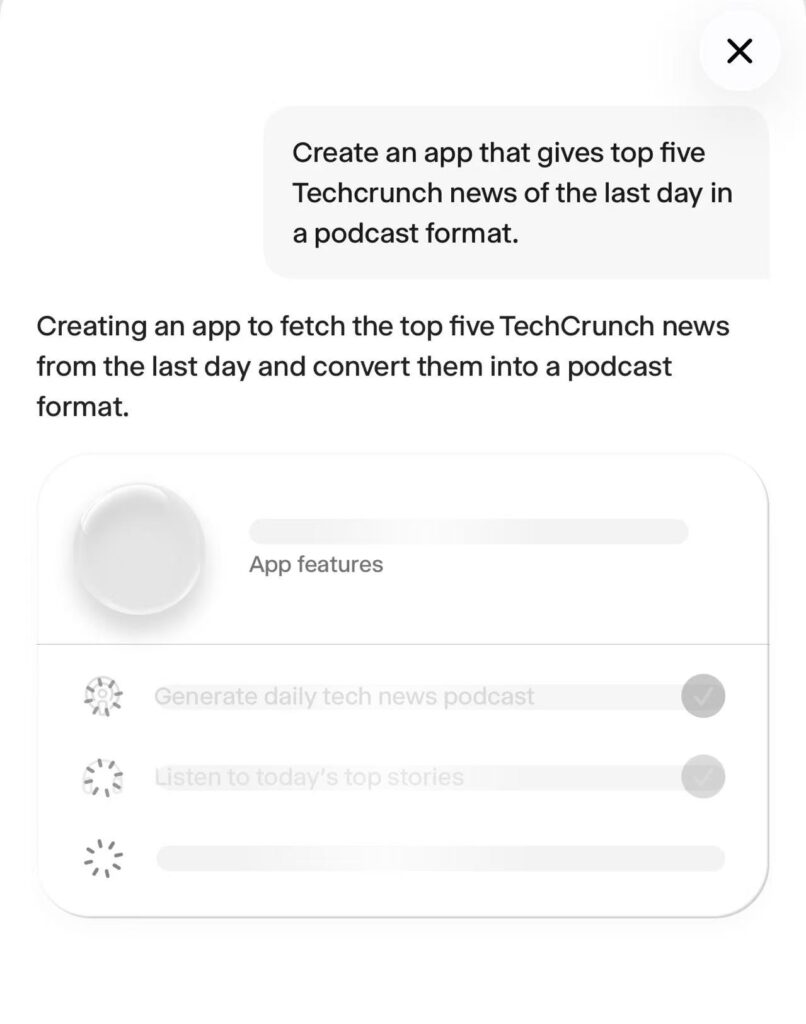

How Wabi Works: Building an AI App in Seconds

The creation process strips away every traditional barrier. Users describe what they want in conversational language:

“Build me an AI therapy app.”

“Create a daily fitness tracker.”

“Make a motivational quote app using lines from The Office.”

Wabi’s AI generates a complete micro-app instantly. User interface, database structure, backend logic, integrations with models like ChatGPT or Gemini, even custom icons. Users never see code. They never configure API keys. They never wrestle with deployment infrastructure.

The platform’s radical simplification extends to integrations. Traditional no-code tools require connecting services manually—authentication flows, permission management. Wabi collapses these multi-step processes into natural language:

“Use my Apple Health data.”

“Connect to my email.”

Done.

This approach represents a fundamental philosophical difference from existing tools. Platforms like Replit, Cursor, and Lovable serve developers who want to build apps faster. They’re “vibe-coding” tools reducing friction for people who already understand software development. Wabi targets a completely different audience: the billions who’ve never coded and never will.

The Social Layer: What Makes This the “YouTube of Software”

The technical capability to generate apps quickly matters. But it’s not what makes Wabi potentially revolutionary. The social layer is what earns the “YouTube of software” comparison.

Apps in Wabi function as social objects. Users can share their creations to a feed, where others can like, comment, and—crucially—remix. Remixing lets anyone take an existing app and modify it, creating derivative versions that might improve on the original or adapt it to different uses. This mirrors how YouTube creators riff on each other’s videos, building culture through iteration and response.

Social discovery transforms app creation from a solitary technical exercise into a community activity. People build things because others are watching, offering feedback, and building on their ideas. Early examples are already gaining traction on X, with users sharing novel micro-apps and iterating on each other’s concepts.

The Birth of a New Creator Class

Anish Acharya from Andreessen Horowitz, an early Wabi investor, frames this as the emergence of a new creator category. He points to 2006-era YouTube as a parallel. Back then, skeptics saw low-quality amateur videos. Visionaries saw the birth of an entirely new internet-native business model that would eventually support full-time creators, production companies, and an entire ecosystem of related services.

Acharya describes Wabi’s potential output as “disposable software”—small, flexible applications you create and discard as casually as opening a browser tab or starting a ChatGPT conversation. Low stakes encourage experimentation. The social dimension encourages sharing.

“The internet has become clinical,” Acharya told press. “We’re all using the same Instagram, the same TikTok. Our home screens look identical. Apps have become uniform. Wabi has the opportunity to bring back some of that punk, weird, early-’90s web energy.”

That nostalgia for the chaotic creativity of the early internet resonates with many who remember when the web felt more personal and strange. Before Facebook, before smartphones, before everything consolidated into a handful of platforms—the internet was full of weird personal sites, niche forums, one-off projects serving tiny audiences. Wabi hints at recapturing some of that spirit, but with modern AI capabilities and mobile-first infrastructure.

The Rise of Long-Tail Software

Traditional app stores can’t serve niche needs economically. Developer time costs too much to justify building apps with limited audiences or unclear business models. A motivational quote app pulling from one specific TV show? Not viable commercially. A fitness tracker customized to one person’s exact routine and preferred progressive overload approach? No market.

But personal needs aren’t less valid just because they’re not scalable. They’re simply unserved by the current economic model of software development. Large language models are upending this calculus entirely.

Gartner predicts that by 2025, over 70 percent of new applications will use low-code or no-code approaches, driven by developer shortages and generative AI capabilities. Wabi sits at the leading edge of this trend, but with a consumer-first rather than enterprise angle.

Real Users, Real Use Cases

The early applications emerging from Wabi illustrate the long-tail potential clearly. Someone built a motivational quote app that exclusively pulls quotes from a TV show they’re obsessed with—a feature no commercial app would ever implement. Kuyda herself built a strength-training tracker because existing fitness apps included too many features she didn’t want. She created it in two minutes while heading to the gym, then continuously adds features after each workout. It now generates new training plans based on her inputs, available equipment, the book she follows, and progressive overload principles.

When her daughter wanted a guessing game, Kuyda built a puzzle app in two minutes using four images. Then she added content about Disney characters. Then she converted it to Italian for language practice. The entire development cycle took minutes across multiple iterations, each responding to immediate needs.

None of these apps would exist in traditional app stores. Even if similar commercial products existed, they’d require tutorials, payment processing, and still wouldn’t match these users’ specific requirements. The perfect-fit nature of personally tailored micro-apps creates immense value for individuals, even though the total addressable market for each app might be measured in single digits.

Software That Compounds Over Time

YouTube let ordinary people create and share videos. Wabi enables ordinary people to create and share software. But there’s a crucial difference: videos typically lose value over time, while software compounds. A viral video from five years ago is mostly irrelevant today. A useful app from five years ago might still be serving its creator every day, growing more valuable as features accumulate.

Acharya predicts this difference will drive the emergence of a new professional class of software creators—analogous to how YouTube evolved from shaky home videos to high-production channels supporting full-time creators. The early phase looks amateur. The mature phase looks professional. The ecosystem develops supporting services, best practices, and economic models that didn’t exist at the start.

Why Now? Wabi vs. GPT Store, Poe, and No-Code Tools

OpenAI’s GPT Store and Quora’s Poe platform already offer ways to create and share AI-powered experiences. Numerous no-code tools promise to democratize app development. What makes Wabi different?

Three strategic decisions: radical UX simplification, deep social integration, and mobile-first architecture.

Simplified UX as Competitive Edge

Wabi made a critical choice: never expose users to code or technical jargon. No API keys. No “connect this integration” workflows. Integrations happen through natural language:

“Use my Apple Health.”

“Connect to my email.”

The platform handles authentication, permissions, and data access invisibly. This might seem like a minor detail. It’s the difference between a tool developers tolerate and a tool consumers actually use.

The Battle of Interfaces

The GPT Store essentially offers customized chatbots. Wabi offers actual applications with interfaces, persistent state, and social features. That architectural difference matters enormously for user perception and behavior. A chatbot feels like a conversation. An app feels like a tool.

Mobile-First as Strategic Bet

Most no-code platforms optimize for desktop workflows because that’s where developers work. Wabi prioritizes mobile because that’s where consumers live. Kuyda’s background is mobile app development, and she believes many creative actions won’t happen on websites. There needs to be an app-store-like organizational layer on mobile, just as browsers organize the internet on desktop.

She cites examples of dating apps built with vibe-coding tools that accidentally leaked sensitive user information—not through malicious intent, but because the creators weren’t professional developers. A reliable hosted platform with built-in security becomes essential when non-technical users are building and sharing applications.

Challenges Ahead

Wabi remains early-stage, with the inevitable rough edges. While creating basic apps is straightforward, debugging can become necessary. One user built a daily dog photos and facts app that started repeating the same dogs after a few days. Another user’s news app labeled all photos “October 1, 2023” regardless of actual date.

Kuyda acknowledges these reliability issues candidly. The underlying models still have limitations, though they improve constantly. Much of the $20 million funding will go toward expanding the product team and subsidizing usage while the company figures out monetization.

The Safety and Infrastructure Challenge

Consumer-grade safety standards matter more for Wabi than for developer tools. When professional programmers build buggy apps, they understand the risks and can fix issues. When consumers create apps for personal use or small communities, they need the platform to handle security, data protection, and reliability automatically.

This creates both technical challenges and significant infrastructure costs. Wabi must provide hosted, secure execution environments for potentially millions of micro-apps, each with different data access requirements and integration needs.

Monetization Remains Unknown

On the business model front, Kuyda is clear about one thing: no advertising. She built Replika without ads despite pressure to monetize through advertising, and she’ll apply the same principle to Wabi.

“Advertising creates dark-pattern incentives and ruins user experience. I like building delightful experiences.”

Potential paths include subscription models, revenue sharing with popular creators, or taking a percentage of transactions if apps facilitate commerce. Acharya believes monetization will emerge naturally once network effects strengthen—similar to how YouTube evolved from “free video hosting” to “creator economy platform” with multiple revenue streams.

The Future of AI Interfaces: Beyond Voice, Toward AI-First Operating Systems

The broader conversation around AI interfaces often fixates on voice interaction, influenced heavily by the movie Her and the success of voice assistants like Alexa and Siri. Kuyda argues this focus is misguided.

Voice interfaces face fundamental limitations. They’re unusable when someone is sleeping next to you. They don’t work well in crowds, offices, or even while walking on a busy street. About 75 percent of Alexa devices now include screens because users need visual information to make decisions and confirm actions.

Voice also struggles with discovery and proactivity. Listening to notifications read aloud is slow and inefficient. Browsing options or exploring possibilities works far better with visual interfaces.

The AI-Native OS Vision

The biggest strategic mistake, according to Kuyda, is building screenless AI devices. If she were building hardware today, she’d create a screen-first, AI-native operating system running models locally. Not an AI assistant bolted onto existing smartphone architecture, but hardware designed from the ground up for local model execution.

This future OS wouldn’t have fixed apps in the traditional sense. Instead, it would create and modify software dynamically based on user needs and context. Apps wouldn’t be static products downloaded from stores—they’d be fluid interfaces generated on demand.

This vision sounds far-fetched until you consider what Wabi already demonstrates: AI can generate functional applications in seconds. Extend that capability to the OS level, running on specialized hardware with sufficient local compute, and you get something genuinely novel. Not a smartphone with an AI app, but an AI-first device where software is liquid rather than solid.

Conclusion: Is Wabi Truly the “YouTube of Software”?

Whether Wabi succeeds in becoming the YouTube of software depends on execution challenges that remain unsolved. Can the platform maintain reliability as it scales? Will the social features drive genuine network effects? Can it find a sustainable business model that aligns creator and platform incentives?

But the vision itself is compelling precisely because it addresses a real constraint in how software gets made. The current model—where 20 million developers build apps for billions of users—is clearly inefficient. Countless needs go unmet because they don’t justify professional development resources. Personal preferences, niche communities, experimental ideas, weird one-off projects simply don’t get built.

Wabi represents a paradigm shift toward software as a creative medium accessible to everyone. If it works, we might see a genuine creative revolution similar to what YouTube sparked for video, Instagram for photography, or TikTok for short-form entertainment. A world where anyone can build and share applications in seconds isn’t quite here yet.

But it’s closer than most people realize. And that’s worth paying attention to—whether you’re a developer worried about your job security, an investor looking for the next platform shift, or just someone frustrated that the perfect app for your specific need doesn’t exist and never will. Unless, perhaps, you build it yourself.

Subscribe To Get Update Latest Blog Post

Leave Your Comment: